- Home

- Colby Cedar Smith

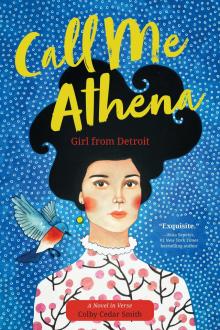

Call Me Athena Page 3

Call Me Athena Read online

Page 3

onto the ground.

I hold an envelope in my hand

There’s no name

no address

no stamp.

I open

the folded paper

and begin to read.

Letter #1

October 7, 1918

My dearest,

I woke this morning afraid. No one knows where you are.

How can I find you?

I don’t even know where to send this.

I pray you are alive.

Always Yours,

Petit Oiseau

Letter #2

October 10, 1918

Love of my life,

Lying in this field surround by smoke and fire, I feel as if our moments together never existed.

How could I have been so happy? Loved you so innocently?

I am sure by now the bed that I slept in is occupied by another wounded man.

Have you forgotten me?

I am afraid I will become what I most fear.

Le Loup

I read

until my eyes blur.

My skin grows cold

with cellar

darkness.

Who were these people?

Where are they now?

Giorgos (Gio)

Komnina, Central Greece

1915

The church bells chime

through the windows

of our house on the hill.

My mother

hums softly,

a song she repeats night

after night

until it becomes a part of me

and the air we breathe.

It feels as if the wind

might come from the sea

and take me on its back

a white Pegasus

or a boat,

with wings

for sails.

I go to school with the mountains

the rocks

the olive trees

that grow in a tangled grove

next to our house.

My teachers are the lizards

that love the dusty soil

and explore the world

with their flicked

tongues.

I go to school

without books

without the brick walls

of a building

with my fifteen-year-old twin,

Violetta.

Wiry and tough.

Her hair braided

in a black crown.

A sweet-smelling halo

curled around

her head.

Mother asks us

to gather quail eggs

from the low grasses and scrub

on the hillside.

We listen

for the chuck-chuck-chuck

of the hen

as she scratches out

hidden hollows

at the bottom

of a tree trunk.

Startled,

she leaps into the air

in a quick burst

of flight.

We see

the brown and white

speckled eggs

camouflaged

against

the undergrowth.

Still warm from

their mother’s breast,

we cradle them

in our palms.

As we walk away,

guilt rips

at my chest.

The thought

of the mother

frantically searching

for what

has been lost.

Giorgos, come quick!

Violetta has found a cave.

There are wild animals,

beasts,

that live in these hills.

Muscled cats, brown bears,

and jackals.

We imagine

the great Spartan warriors

of Thermopylae.

We enter the mouth of the cave.

All we find

is a γίδα (gída),

a small goat.

Her bell jingles

from a leather strap

wrapped

around her neck.

She is staked to the ground.

Miles of wilderness.

No freedom.

A circle of grass

mowed down

around her.

We name the goat Alethea

It means truth.

She is stubborn.

She will eat your clothes.

And also trash.

You have to watch her closely.

She’s always trying

to get away

with something.

I scratch her

and she curls her head closer

to my hand.

When I stop

she stares at me

with her vertical

amber eyes.

A creature

from the underworld

who knows

everything

but will tell me

nothing.

The old men in the village

are sighing

and talking about war.

The elders know what is coming.

Young men puff up their chests.

They will join the army.

I do not want to fight.

Why do I need to carry a gun

to prove

that I love my country

and my home?

Violetta ties her skirt

in a knot between her legs.

She wants to wear

pants instead

of the dress and apron

she must wear

everyday.

She puts on my vest and hat

when our mother is out.

Ώπα! (Hopa!), she says.

I look very brave!

One day, Violetta falls asleep

wearing my clothes.

My mother comes

home.

She spits

in Violetta’s face,

Our house will be shamed

because of you!

I wipe the tears

from Violetta’s eyes.

She would be

a very brave boy indeed.

When my mother’s eyes are red

like the juice of a blood orange,

that is how I know

she has been crying.

She tries to do it in secret,

but we all know it happens.

She misses my father.

She never says

that she loved him,

only that he was good

to her.

Most of the men from the village

are not good to their wives.

One time, I saw a man

throwing stones at his wife

while she covered her head

with her hands.

One day, I will become a man.

I will try to be good.

There are stories

of dolphins

and mermaids

who push

their heads

out of the water.

Offer

>

their breath

to men

who are

drifting.

Sometimes

I wonder

if this happened

to my father.

Perhaps

they saved him

and took him

to an island

with fresh water

and fruit growing

on trees.

I like to think of this.

Rather than his boat

on the bottom

of the sea.

My sister and my mother

clean the house

bake the bread

feed the animals

milk the goat

tend to the garden.

I am not allowed to help.

If I lift a plate,

my mother slaps my hand

and screeches,

Women’s work!

I hear the crack

of my mother’s voice,

Violetta! Come!

I watch

the anger rise

on my sister’s pink cheeks

like she has been struck

by a willow switch.

My mother has found a match

for Violetta.

She clasps her hands in triumph

and grins as widely

as a fisherman’s net

spread across

a harbor.

He’s from a good family!

I have been listening at the market,

I have been talking to the women.

She will go to a good home

to a man

who will care for her!

We will wait

until you turn sixteen,

my mother says.

Her hands

placed firmly on her hips.

My sister puts her cheek

on the cool

wooden table.

Mother spoons

large portions

of tomatoes, feta,

and beans

onto our plates.

She does not see

that my sister

has completely

lost

her appetite.

I find my sister

in the garden.

She’s holding a small bouquet

of wildflowers.

I don’t know why

I picked these.

They will wilt by tomorrow.

I put my hand

on her shoulder.

Think of all the words

that could comfort.

None of them seems right.

She holds the flowers

out to me.

They would have been happier

staying right where

they were.

My father told me

the three most important

things in life:

the boat, the sea,

the family.

That’s all you need.

My father is missing

My sister is about to leave me.

And I don’t have

a boat.

Jeanne

Saint-Malo, France

1915

The smell of the sea

climbs the walls

of our city

like a salty,

dangerous

pirate

who steals

into my bedroom

and whispers

in my ear.

Come with me.

The night turns me

into a sparrow.

Wings tipped

with golden arrows.

The stars sing

in the firmament

a song that belongs

to me alone.

Come home.

We live in a house

on the top of a hill

filled with beautiful

things

and a maid

to dust them.

We live in a house

with a small black dog

named Felix

who eats

out of a crystal bowl.

We live in a house

filled with visitors

who drink champagne

and dine on oysters

and canapé

in the rose garden.

We live in a house

as old as the cathedral

with a balcony door

that opens

to the emerald sea.

We live in a house

filled with books,

tales of adventures

and voyages.

I wonder

if these stories

will ever be written

about me.

A letter arrives

Papa breaks a government

red wax seal

to open it.

He is needed in the war effort.

They know

he will be a wonderful doctor

in the French Foreign Legion.

It is time

for him to fulfill his duty

to his country.

He will leave

the day after Christmas.

He throws the letter

into the fire.

It crackles and spits

and rises up the chimney,

black as smoke.

It is mid-December

and we gather

with our neighbors

for la fête de Noël,

our winter festival.

It is my favorite day

of the year.

We eat crêpes filled

with sugar and jam

and galettes saucisses,

spiced sausages.

Drink cider and chouchen,

a honey brew.

My father’s friends

pat him on the back,

wish him luck.

Neighbors

thank him for his service.

The music begins.

We laugh and breathe hard

as we dance and sing

in a circled chain

to the bagpipes, the accordion,

the fiddle, and the drum.

Two sisters join the stage

and sing

an a cappella song.

We stop to listen.

Their voices wind

around each other,

a threaded bobbin

whirling inside

a spinning wheel.

They sing le chant des marins.

A sailor’s song

for our people. 7

The Bretons

are wild

like the purple heather

that grows

on our rocky shore.

The Bretons

are sweet

like the gold

we squeeze

from the depths

of the honey’s lore.

The Bretons

are brave

as the northern wind

and we know that

we must pray.

To the Lord, our God

to keep our ships

from that dark

and watery grave.

O keep us from

that watery grave.

O keep us fr

om

that grave.

Maman closes her eyes

I see tears escape.

We listen to the music,

but I know we are both

thinking of the boat

that will take Papa

to a country

far from here.

She hugs me close.

My head fits perfectly

in the curve of her neck.

I can hear

her heart

beating.

A lonely bird

trapped in a cage.

The day before

my father leaves,

the townspeople gather

to see Louis Blériot

Call Me Athena

Call Me Athena