- Home

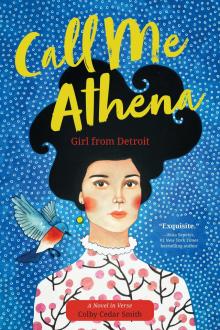

- Colby Cedar Smith

Call Me Athena Page 2

Call Me Athena Read online

Page 2

down the road.

The rest of us

getting covered

in dust.

When we get to school

two boys

are dragging each other

through the yard.

Gus climbs on top

and pulls them apart.

He winds up with a bloody lip

before the bell rings.

We file into

the classroom.

I hear Evie Williams

talking about me.

Two sizes too small!

You can see EVERYTHING!

Her friend Fay

looks at me

and mouths

an apology.

Evie stares

at the popping buttons

on my dress.

Eyes wide

like the barrel

of a gun,

loaded

and ready

to fire.

My whole body

feels hot

and panic

swells my brain.

I am a sack of grain

with a target

painted

on my chest.

I settle on a bench

between Marguerite

and Elena.

Elena’s parents

are from Romania.

She was born

in America

just like us.

Elena’s cheeks

are ripe, round

plums.

Her black, straight hair

smells like cooked

cabbage.

We link

our elbows together.

If our school

were a garden,

I think Elena,

Marguerite, and I

would be growing

on the very same

vine.

We rise and pledge

allegiance

to the flag

of the United States

of America.

We all speak

in different accents.

Our voices ring

in unison.

Liberty and justice

for all.

For a brief moment,

it feels like

we might

have something

in common.

Then I see Evie

sneering at me again.

CAREER

Our teacher, Mrs. Patterson,

scribbles the word

on the blackboard.

Asks us to write

a paragraph about what

we want to do

when we graduate.

What are your dreams?

My brothers

start writing immediately.

John wants to be a pilot.

Gus wants to be a soldier.

Jim wants to build skyscrapers.

Marguerite wants to be

a homemaker.

I don’t write anything.

Good Greek Girls

know better than to dream.

Good Greek Girls

never speak before spoken to.

Good Greek Girls

never ride bikes.

Good Greek Girls

marry at a young age.

Good Greek Girls

take care of the babies at home.

Good Greek Girls

don’t have jobs.

Good Greek Girls

don’t dance and smoke and drink.

Good Greek Girls

never complain.

I don’t know if I want to be

a Good Greek Girl.

My mother calls her daughters

to the kitchen.

We carry serving dishes

filled with

stuffed tomatoes and peppers

and large bowls

of cucumber salad.

We eat outside

in my father’s garden

under the climbing grapevines.

Amidst the aroma

of the blooming roses

and carnations

planted

to remind him

of Greece.

My mother loves

when we eat and drink

and laugh together

at the table.

After dinner,

she serves

the bright-red cherries

that we canned

last fall.

She ladles them

into small crystal bowls

with silver spoons

souvenirs

memories

from her life

in France.

I saw a fight in town

my brother Gus says

from the corner of a full mouth

as he reaches

for a second helping

of cherries.

My mother glares at him.

A real doozy.

The whole works.

One guy was calling

the other guy names.

He didn’t like it much.

Pulled out a blade.

The crowd gathered in a circle

around them.

I didn’t stay

to see how it turned out.

He shovels more fruit

into his mouth

and doesn’t notice

the bloodred juice

staining his chin.

My father holds his worry beads

clicks them

between his forefinger

and his thumb.

Too many men

out of work.

His voice

accents each word

like the beads

on the string.

The factories

were the only thing

keeping peace

in this town.

My mother puffs air

out of her mouth

in exasperation,

Now everyone is praying

that the immigrants

will go home.

This is our home.

What would it feel like

to have blond hair and blue eyes?

My sister asks

with a dreamy voice.

I look at Marguerite’s

big, beautiful, black, curly hair.

Her amber eyes

and olive skin.

I can’t help laughing.

What would it feel like

to have a name

like Smith or Jones?

I retort.

What would it feel like

to have great-great-grandparents

who arrived on the Mayflower?

she giggles.

What would it feel like

to drink Coca-Cola

at the beach

under an umbrella?

I act like I’m opening

a parasol.

What would it feel like

to not speak Greek,

eat Greek food,

go to Greek church?

Normal?

my sister asks.

“Normal” is not a word

I have ever used.

I say with a flourish.

I take her hand

and spin her

ar

ound the yard.

There’s a pharmacy and a soda shop

on the corner.

Marguerite and I

don’t have the ten cents

to buy a copy of

Ladies’ Home Journal

so we stand in the aisle

and suck

penny candies

and read the articles,

“Keep That Wedding Day Complexion” 5

“A Man’s Idea of a Good Wife”

“Hints and Suggestions for Helpful Girls”

Just as we are about

to dig into

a particularly juicy story,

“Promiscuous Bathing” 6

Mrs. Banta,

the owner’s wife,

finds us huddled

in the corner whispering.

She sweeps us out

of the doorway

with her broom.

We look into the shop windows

to examine ourselves.

Dab our lips and cheeks

with red rouge.

We pose like starlets

in the magazine.

Jazzy flappers.

Imagine

we have short, cropped curls

and flasks

tucked into

our knee-highs.

Girls who drive

in cars with boys

and dance.

Come look!

I pull Marguerite’s arm

until we’re standing

in front

of a dress shop.

A mannequin

with a surprised expression

gestures

toward the heavens

like she just felt

the first

drop of rain.

An emerald green

evening dress

draped

across her form.

Rose beige

patent leather

T-straps.

A gardenia

in her hair.

Oh, Marguerite!

Isn’t she divine?

She’s beautiful.

I wish

we had matching dresses

just like this

and a place to wear them.

I wish we had new boots.

I look down

at our worn boots

and my dreams

fizzle.

The clouds turn gray

and disappointment

falls

from the sky.

Our boots are practical

Black.

Sturdy.

Thick soles.

They’re meant to last.

We will wear them

until the thread unspools

and the leather cracks.

Until the rainwater

soaks through

and our bones

are cold.

We will stuff them

with newspaper.

It won’t make a difference.

Only then

will we beg our mother

for a new pair.

She will look

at all of our shoes

and decide.

Whose feet are the coldest.

Whose lips are the bluest.

Who needs the warmth

the most.

After church on Sunday

there is a man waiting

at the carved doors

of the entryway.

My father embraces him.

Dimitris takes my hand

and brushes it

with his dry lips.

His striped vest

bulges

with his belly fat.

Dimitris tells me

he owns a shop,

a haberdashery.

He sells men’s clothing.

Silk and felt hats

of all shapes and sizes.

Fabric and thread

ribbons and zips

buttons and clasps

and small notions.

Dimitris lives alone.

In a sad house

that smells like

soup.

I tell my father

if that man

comes in the front door,

I will go out

the back.

My mother yanks me

into the kitchen.

Control your temper.

My sister

is peeling carrots

at the table.

In my frustration

I blurt out,

What about Marguerite!

Why doesn’t she

have to get married?

As soon

as the words

come out of my mouth,

I feel sorry.

Marguerite

looks up from

her work

with a panicked

expression.

A fox

caught in a snare.

I am more concerned

about you, Mary!

my mother snaps.

What man

would choose a girl

like you?

I imagine the day of my wedding

I walk down the aisle

toward a man

I do not love.

Surrounded

by hallowed images.

The priest blesses us

as the chorister chants,

Ησαϊα χόρευε,

η Παρθένος έσχεν εν γαστρί.

(Isaïa chóreve,

i Parthénos éschen en gastrí.)

Isaiah dance,

the Virgin is with child.

He signs the cross

and lays a wreath

of flower buds

on my black curls.

Another

on the gray hair

of my groom.

Entwined together

by the Father, the Son,

and the Holy Spirit.

We drink from one cup.

Servants of God.

Marguerite is lying on her back

in the garden.

Her arms and legs

spread like a starfish

on a rock.

I lay down beside her.

We look like stars

in the same constellation.

I don’t want to leave.

I don’t want to get married.

I’m happy in this home

with you.

She holds my hand

and says,

It can’t stay the same forever.

Even if

we wish it could.

I feel like someone

has thrown a stone

into the heavens

and smashed the stars.

We are falling

from the sky.

I lie for a long time in the grass

even after Marguerite has gone.

I turn on my shoulder

and spy a shovel

lying on the ground.

I stand and pick it up.

Walk down the cellar steps

to return it to where

it belongs.

The cellar smells

of the dark, moss, fungus

that lives

in the packed dirt f

loors

of this subterranean space.

Shelves hold

boxes of potatoes,

garlic, apples, and onions.

I lean

the heavy shovel

against the wall

and it falls

with a loud crash

onto a shelf.

Boxes topple down.

Heads of garlic

fly across the floor.

I groan and bend to gather

the rolling bulbs

when I notice

an ancient wooden box

covered in dust.

The clasp sprung open.

A stack of letters

tumbling

Call Me Athena

Call Me Athena